Published on the BBC News website on 3rd July 2014

Story by David Shukman

A major study into the potential of fracking to contaminate drinking water with methane has been published.

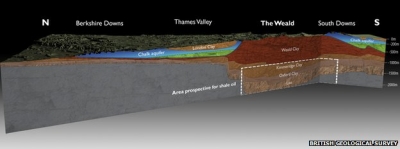

The British Geological Survey and the Environment Agency have mapped where key aquifers in England and Wales coincide with locations of shale.

The research reveals this occurs under nearly half of the area containing the principal natural stores of water.

The risk of methane being released into drinking water has long been one of the most sensitive questions over fracking.

Sealed wells

The study highlights where the rock layers may be too close to the aquifers for fracking to go ahead.

It finds that the Bowland Shale in northern England – the first to be investigated for shale gas potential – runs below no fewer than six major aquifers.

However, the study also says that almost all of this geological formation – 92% of it – is at least 800m below the water-bearing rocks.

Industry officials have always argued that a separation of that size between a shale layer and an aquifer should make any contamination virtually impossible.

They say that wells are sealed with steel and concrete as they pass through water-bearing rocks and that any fissures created by fracking far below would be highly unlikely to spread through hundreds of metres of rock.

Environmentalists say that the processes of drilling and of fracturing rock inherently carry the risk of polluting a vital resource.

Analysis of the Weald Basin in southern England shows that the uppermost layer of oil-bearing shale is at least 650m below a major aquifer.

Dr John Bloomfield, of the British Geological Survey, said the maps could serve as a guide for regulators and planners.

“We’ve identified areas where aquifers are in relatively close proximity to shale units and any developments would have to be looked at particularly carefully,” he said.

“It’s no surprise that the same system of sedimentation that produces shale also produces limestone which is excellent for storing water.”

Ruled off-limits

Aquifers such as the Oolite, which runs from Yorkshire through the East Midlands to the south coast of England, are often in direct contact with a shale layer.

Maps showing the relative proximity of shale layers and aquifers are available on the British Geological Survey website.

So far, no definitive distance for separation between shale and aquifers has been set but a limit of 400m has been suggested because water from below that depth is rarely considered drinkable.

In some areas, shale layers rise closer to the surface – and the assumption is that these would be ruled off-limits.

The Environment Agency says it will not allow developments to go ahead if they are too close to supplies of drinking water.

Meanwhile, the BGS has carried out a survey of methane in drinking water in all areas of the country where fracking may happen.

Low levels of the gas occur either naturally – from bacterial activity – or from manmade sources such as landfill sites.

Dr Rob Ward, director of groundwater science at the BGS, said the aim was to provide a baseline understanding before any fracking starts.

“In the United States, they didn’t carry out a baseline survey before the industry took place and that has resulted in controversy and uncertainty about the source of methane in drinking water,” he said.

“We now have a window of opportunity to collect data on methane before any industry goes ahead. If we see increases in methane in groundwater which may be attributed to shale gas, we’ll be able to spot those.”

Follow Havant FOE